happiness and time

“But simultaneously he situates himself in relation to time. He takes his place in it. He admits that he stands at a certain point on a curve that he acknowledges having to travel to its end. He belongs to time, and by the horror that seizes him, he recognizes his worst enemy. Tomorrow, he was longing for tomorrow, whereas everything in him ought to reject it. That revolt of the flesh is the absurd.” ~Albert Camus

The myth is in time…

Circulated stories create a cultural mythos. To trace the discourses of workplaces happiness and meaningful work, and their discursive formation, means looking for stories distributed on happiness and purpose-driven work. The narratives are often political, concern social and material capital, and they develop, establish, and in this case, create generational understanding of labor identity. The discursive formation of workplace happiness and meaningful work is an important cultural mythos in the “care of the self.”[i] Where did the message of workplace happiness emerge? What discourses, disciplines, modes of information, and networks speak back to Camus’s hopeless choice: suicide of the mind or imagining ourselves happy in the break from work? Even with choice, Camus insists we will spend time in dull, repetitive, purposeless labor. Workplace happiness would mean we do not need to wait for leisure (walking down the hill to return pushing the boulder on Monday) because finding meaning and happiness at work negates the necessity of leisurely weekend. Recall the mythical statement from Confucius and Mark Twain (which neither said): “Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life.”

Many of the stories involve disparate but intertwined concepts such as health insurance, class, consumerism, as well as philosophical ideas such as rationalism and personal freedom. Like most discursive formations, the complexity is challenging to convey, especially in a short essay reflecting briefly on this idea. My oversimplified highlights deserve more thorough explanation and workplace happiness, and meaningful work, are well researched topics. While labor movements, such as unionization and worker’s rights span a few centuries, the emergence of discourses on workplace happiness and meaningful labor are more recent.

The concept of holistically helping employees, although not new, rose in popularity as more companies were required to pay for health insurance and began to peak in the 1970’s. The first Employee Assistance Program (EPA) in the 1950’s sought to help employees with addiction and mental health issues. “Worksite wellness programs have developed largely in response to cost-containment efforts combined with the worksite health promotion movement.”[ii] By offering EPA’s, companies demonstrate employee wellness to insurance industries, and healthy employees will use health insurance less and work more efficiently (or so the story goes). In addition to health insurance, the rise of the middle-class and white-collar jobs in the 1950’s and beyond required a new type of story about work which included intrinsic happiness or meaningful work, and “it was convenient for a rising class to believe that working people had no reason not to be happy and that laziness and bad habits disrupted not only performance but also contentment.”[iii]

The escalation of happiness built on the existing culture, but there were other contributing factors. The transition from a largely manufacturing to a white-collar economy played a role, providing more settings in which managers could see happiness as a business advantage. Consumerism was central. All sorts of advertisers (a newly distinct profession) discovered that associating products with happiness spurred sales. This is what most clearly explains why the intensified happiness culture of the mid-20th century has, in the main, persisted to the present day. We’re still supposed to be smiling.[iv]

The pursuit of happiness is an enlightenment concept and considered a rational demand by the individual of civilized society: “a self-evident truth.” Previously normalized rationality of happiness as a “right” provides further credence to the narratives on workplace happiness emerging from corporations and shifts in economic class. Being happy and finding purpose in work is a rational desire. However, what happens when the world is irrational? What if we choose a meaningful job but are unhappy? The individual, another modern construction, still has choice according to existentialist philosophers.

Camus, an existentialist, questions reason’s ability to satisfactorily find answers to the universe and humanity’s purpose in the cosmos. Camus wrote Myth of Sisyphus after World War I, the Spanish flu, the Great Depression, and during World War II. Those major events spanned just over thirty years. A large portion of the global population was forced to acknowledge the futile and delicate position of humanity. Scientific rationality failed to halt the atrocities of war, genocide, pandemic, and nuclear holocaust. For Camus, the absurdity of life in the early 20th century was further demonstration of the irrational and indifferent universe. Camus’s response is the individual must create their happiness; perspective, attachments, and conditions are subject to individual belief. In other words, we create our story. If workplace happiness and meaningful work cannot be rationalized, no worry, we as the individual still have a choice to create our own meaning. The world can be absurd, irrational, and unfair, but we can still construct happiness and make meaning ourselves. Meaningful work is then either rational, or if irrational since both the universe and corporations are indifferent to your life, happiness and meaningful work is personally constructed; the story of being happy and fulfilling a purpose in your labor is indisputable and pervasive.

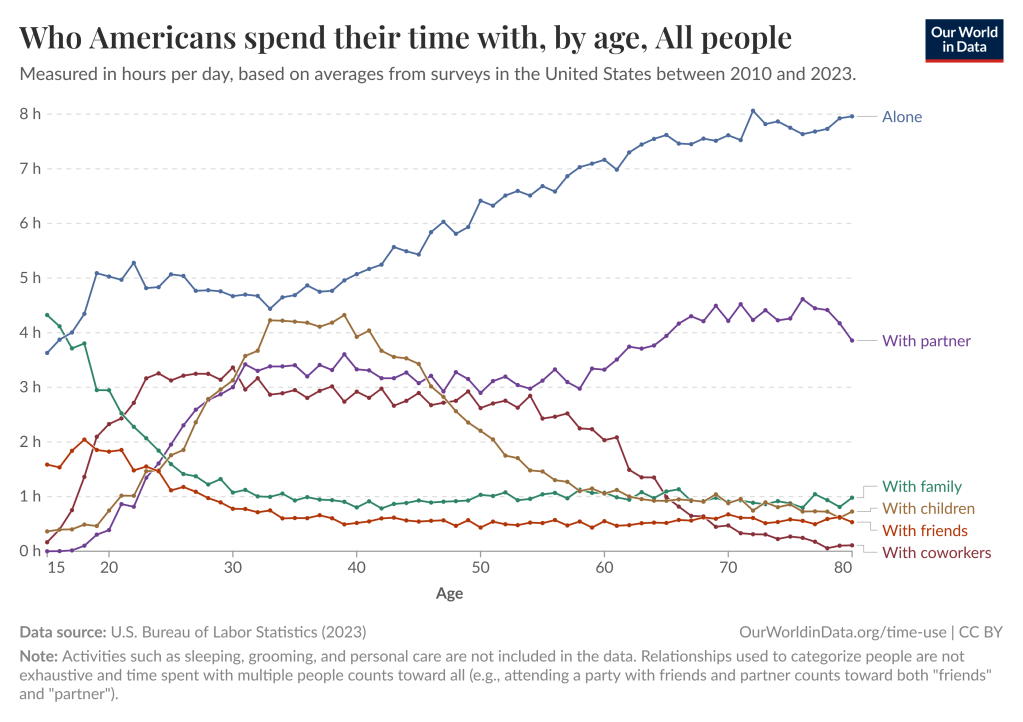

These discourses of workplace happiness and meaningful work are even more convincing when we realize the amount of time spend working in a lifetime because working is our cosmic reality. In truth, time is our most vital difference from Sisyphus. He has an eternity of “leisure” (and of boulder pushing), while our time is finite. Workplace happiness and meaningful work are grounded in our knowledge of time. In our lifetime, people will spend a significant time with their coworkers, second only to partners. From fifteen to sixty, we spend most of our time sleeping and working.[v]

A significant amount of human life is spent working. Recognizing time is limited, and fully aware of the hours in the day spent commuting, working, beside coworkers, and mentally working at home, meaningful work is a rational desire. “The cultural commitment to happiness promoted new narratives to associate work with happiness, through experiments in human relations techniques or just piped-in music. It inspired new workplace standards that instructed white-collar employees and salespeople in the centrality of cheerfulness”[vi] We are not cursed as Sisyphus, subject to endless toil, only finding happiness when we walk down the hill. He has infinite chances to walk down the hill, pausing from labor. Our experience is quite different according to the data, and as Camus illustrates, absurdly finite. Strangely the existentialist argument also reinforces the rational logic that to be happy, one must be passionate about their work. The data is evident, we must work A LOT; therefore, we need to be happy.

The narratives of workplace happiness and meaningful work come from a variety of locations from health insurance, class, stoicism, religion (dharma), duty and obedience, self-help, higher education, academic disciplines, workplace structures (HR and unions), identity politics, enlightenment, means of production, consumption, idealism and mysticism, absurdism, social capital, and all become part of a discursive formation. For to live in the age of information is to have all the reminders of our meaninglessness, while also perpetually absorbing narratives of self-creation – the fear of futility fuels the consumption of a purpose-driven-life.

We rationally want to be Gilgamesh, knowing the Sisyphus existence is more likely in the absurdity of our cosmos. We make a myth of hope in happiness, and the data supports the narrative. We spend the majority of our time with colleagues laboring, working in a space of production. The happiness is the meaningfulness measured not just by job approval but by reward, social and material capital, and by our existential worth in the cosmos, which is a personal choice. The stories of meaningful work are widespread. Heroic labor identities are first responders, doctors, nurses, scientists, innovators, CEO’s, and leaders. Tradesmen and craftsmen maintain infrastructure and are the “backbone of our country.” Farmers feed our nation. Local business owners are entrepreneurs, risk takers and their work maintains hope in individual achievement. Engineers create. Celebrity is born form followers (social capital). Buying power, purchasing freedom, and financial security are interwoven in these heroic, labor identities. We serve with honor and for reward, and if we work with purpose, well then, our time laboring is consumed by meaningful work.

Identifying spaces and places where cracks in the narrative exist is where my exploring is leading. For instance, the use of the term “essential workers” during the global, COVID pandemic illustrated a crack in the discourses. Essential workers vary by sector, but the term is a privilege of cultural necessity in a time of crisis, uniquely essential workers often do not come with material capital (teachers and nurses), and sometimes become a victim of finnicky, social capital (e.g. healthcare workers during the pandemic).[vii] Their heroic nature of essential workers during a pandemic quickly turned to resentment as the crack in material and social capital became evident during the recent pandemic. A significant number of teachers and health care workers left the profession – they may be called “essential” but the material and cultural reality was quite different.

Regardless of enlightenment or existentialism, culturally mythos are manufactured by the circumstances culture determines necessary. The way the cultural cosmos is organized, the stories we circulate, creates the boundaries of belief. Our work appears necessary enough to be locked into Sisyphus’s choice, or we can opt for a perspective of rationality, mysticism, or stoic fatalism when it comes to our labor identity. All of the perspectives are the limits to what we know possible. Possibly I’m exploring this discursive formation to find gaps – the liminal spaces where workplace happiness and meaningful labor is impossible or illogical, to demonstrate labor identities are cultural mythologies. Critique identifies conditions of possibilities unknown because the story does change over time, and its changing right now.

In 1993, 61% United States Workers surveyed indicated work was “very important” in comparison to 2022 to only 39% of those surveyed in the US found work “very important.”[viii] Our time is still our own because if “you love what you do, you won’t work a day in your life” but what if the cultural mythos is challenged? Narratives across channels, propaganda, disciplines, social media, community (digital and present), information mediums in all their different states and spaces within the network of cultural mythos are stories; we are a node in the network. Employees and labor identities are written, manufactured and recirculated. What happens when the narrative evolves? How do we reconcile when our meaningful work can be replaced by technology? The evolving rhetoric around Artificial Intelligence (AI) is emerging in contrast to, and possibly in support of, workplace happiness and meaningful work. The rhetoric about AI demonstrates how stories emerge and evolve in real time and how cultural mythos change.

[i] Foucault, Michel. Ethics: Subjectivity & Truth. Edited by Paul Rabinow. Vol. I. United States of America: The New Press, 1997.

[ii] Reardon, J. (1998). “The history and impact of worksite wellness.” Nursing Economics, 16(3).

[iii] Stearns, Peter N. “The History of Happiness.” Harvard Business Review 90, no. 1/2 (January 1, 2012): 104–9.

[iv] Stearns, Peter N. 2012.

[v] Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban, Bastian Herre, Tuna Acisu, Charlie Giattino, and Max Roser. “Time Use.” Our World in Data, November 29, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/time-use.

[vi] Stearns, Peter N. 2012.

[vii] Stokes‐Parish, Jessica, Rosalind Elliott, Kaye Rolls, and Debbie Massey. “Angels and Heroes: The Unintended Consequence of the Hero Narrative.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 52, no. 5 (September 2020): 462–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12591.

[viii] Integrated Values Surveys (2022) – with major processing by Our World in Data. “Very important – Integrated Values Surveys” [dataset]. Integrated Values Surveys, “Integrated Values Surveys (IVS) Version 3” [original data]. The European Value Study (EVS) and the World Value Survey (WVS) are two large-scale, cross-national, and repeated cross-sectional longitudinal survey research programs. Since their emergence in the early 1980s, the EVS has conducted 5 survey waves (every 9 years) and the WVS has conducted 7 survey waves (every 5 years). Both research programs include a large number of questions, which have been replicated over time and across the EVS and the WVS surveys. Such repeated questions constitute the Integrated Values Surveys (IVS), the joint EVS-WVS time-series data which at the moment covers a 40-years period (1981-2022).