In the Beginning

What do you want to be when you grow up? What is your dream job? What do you do for a living? What kind of work do you do? Where do you work? How long have you worked there? How do you like your work? Where do you see yourself in five years? How many hours do you work a week? What do you bill an hour? How did you get into that line of work? Where did you go to school? The answers to these questions are our cultural origin story. The narrative of life, of capital and cultural holdings, of passion and purpose, of who we are – these are the questions that create the cosmic order of our selfhood.

Our stories begin from the position of our work, and our labor identity, or the precursor to our labor identity – birthplace, childhood, college and first jobs – set the stage (space), character (type of work) and success (culturally predicted belief) shape our cosmic myth of work. Some types of work carry heritage identity: my family farmed for four generations, or my grandfather owned this business, or all the women in my family are healthcare, both parents are teachers, etc. Heritage labor identities begin, often inflexible, before conception, and the boundaries of the life unlived are drawn before the beginning. First generation to college, first generation to trade, first in my family to do _____, redraw maps and explore new worlds like a conquering hero for their families. The cosmology of our labor identity sets a foundation for heroic deeds albeit with predetermined outcomes because like all heroes past and present, the success of our deeds, or work, is culturally defined. We may believe work is a “choose your own adventure” but, hidden borders, places “there be dragons,” and the location of our birth influences our labor identity. I’m not going to be an Orthodox Priest because of my gender and location, but I can still work as a spiritual leader if I choose. I can find purpose in my work and should which is the most vital aspect of all cosmic myths: provide purpose. For work, manufactured choice is essential to our cosmology.

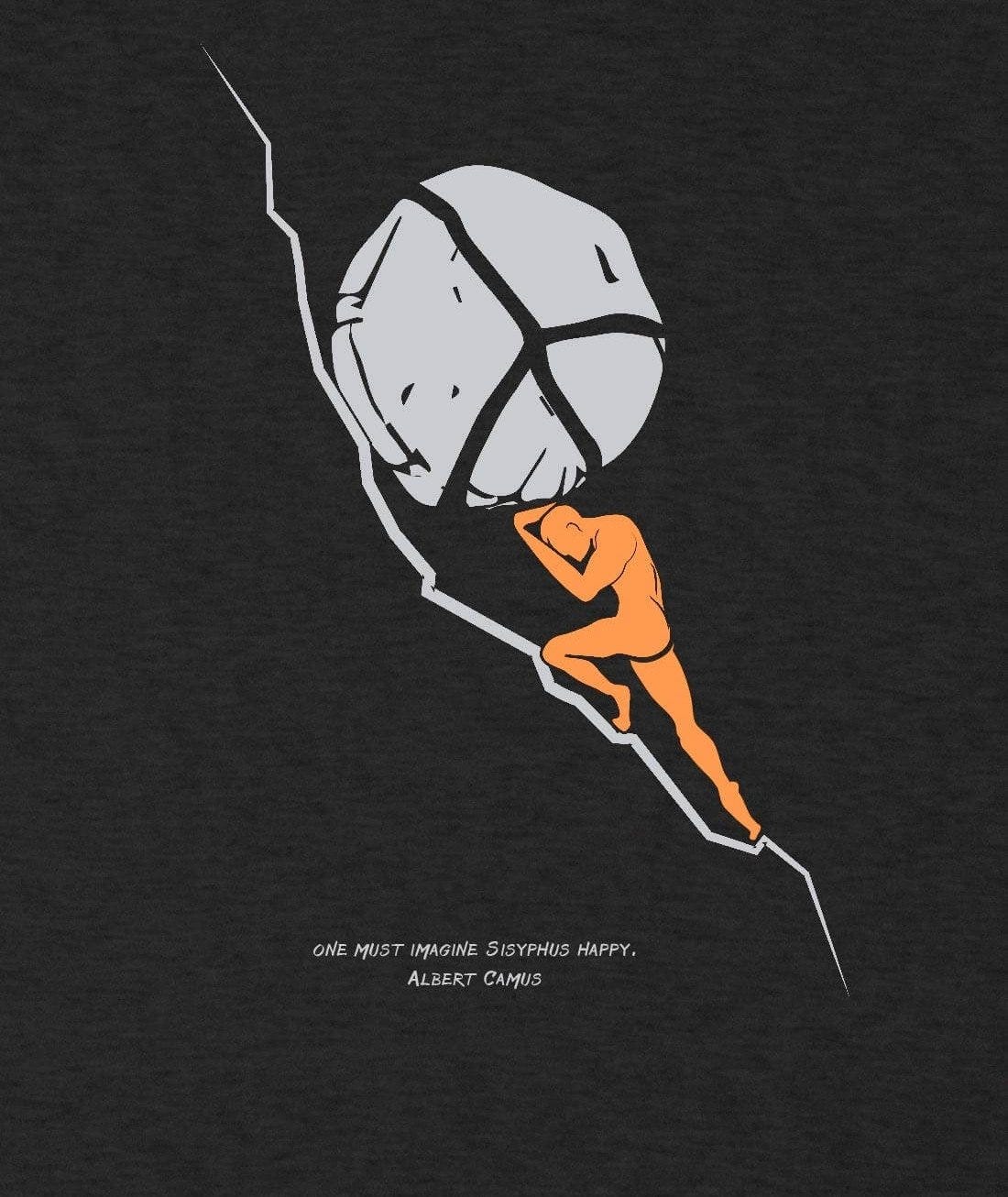

In his essay on The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus wrote: “The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.” Sisyphus, the defiant king, whose repeated hubris lead him to an eternity of punishment, endlessly pushing a boulder uphill. For Camus, the absurdity of humanity is our finite, yet conscious, existence paired with repetitive, purposeless work that engrosses most of our finite lifetime. Our only happiness, like Sisyphus, is the short walk back to the bottom of the hill: the moments of leisure, seeming freedom, between times of work. A person must either find pleasure in the turn from work (leisure), or a suicide of the mind. Admittedly, the choice is absurd, and even then, we must imagine Sisyphus is happy.

Sisyphus defied the gods on more than one occasion, specifically trying to thwart death. Camus compares his eternal punishment to “futile and hopeless” labor: the greatest punishment the gods could give. In a finite existence to be subject to pointless work is heaping insult onto the injury of our inevitable death. We as humans can never truly know the meaning and purpose of the universe; we will die; and we are conscious enough beings to understand the uselessness of the memo, report, project, or the email we just sent.

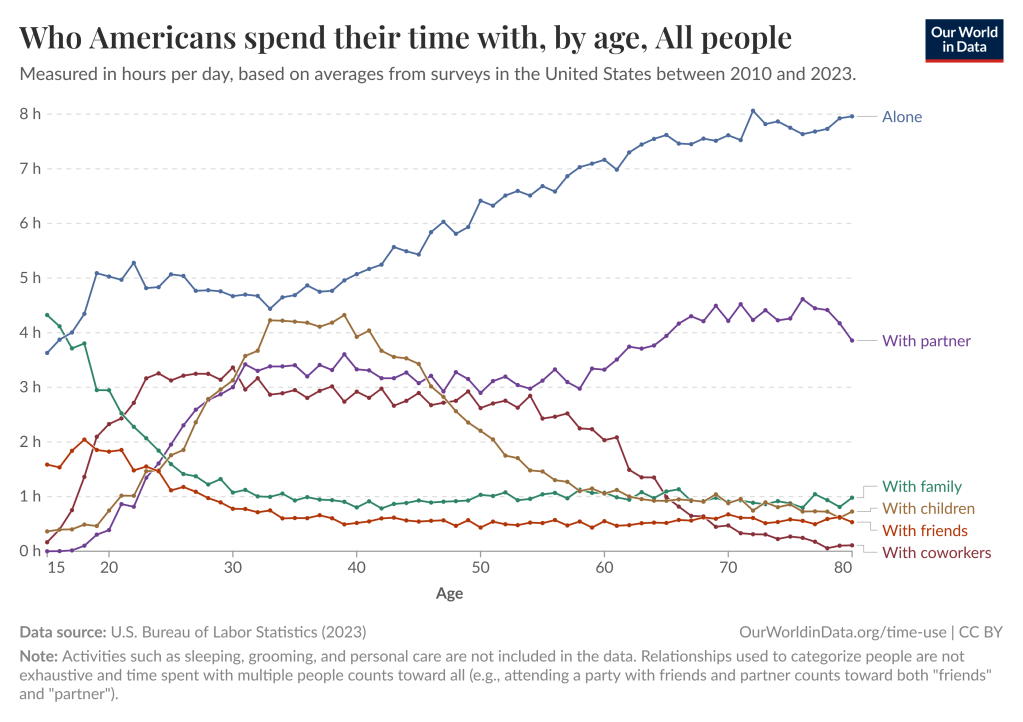

Leisure, the liminal spaces between working hours, is our only hope according to Camus, which in itself becomes commercialized (another topic). Camus’s bleak outlook on our brief life is dissatisfying. My project traces the discursive moment, where “happiness” and “purpose” at work became popularized and necessitated. When ownership of the means of production is out of reach, even understanding your role in helping society, is not enough to sustain 40+ years of work. Purpose in work is the seemingly reasonable solution to the finite life. The worker must imagine themselves happy.

Workplace happiness and purpose driven labor is a discursive response to the hopelessness of labor and the briefness of leisure. The discourses of workplace happiness demonstrate an evolution of the labor identity storyline that champions choosing work that provides life-fulfilling meaning, choosing disciplines of passion, understanding socially recognized professional identities, and a story of a hero – the worker who finds meaning in their work, who can live and breathe the job, and “loves what they do so they never work a day in their life.” This hero worker is a doctor, engineer, innovator, entrepreneur, social worker, therapist, teacher, lawyer, civil servant, professor, investor, scientist, etc. They have title we know. Their choice was altruistic and often predestined – they were always good at ____. They loved Legos as a kid and built things with their hands; they were meant to be an engineer. Their mother was a nurse, and they want to work in healthcare to help others heal. They are going to cure cancer in biomedical research. They are actual heroes, striving to help their fellow man. Their minds are fulfilled at work and in leisure. They are not condemned to be Sisyphus because rolling the rock is actually “a dream come true.” A dream prewritten in a story consumed from birth (what do you want to be when you grow up) about our labor identity.

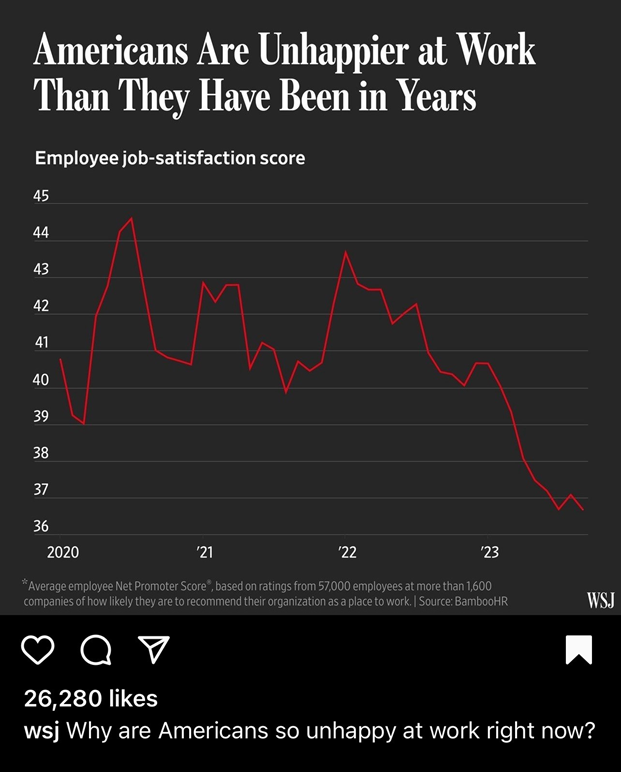

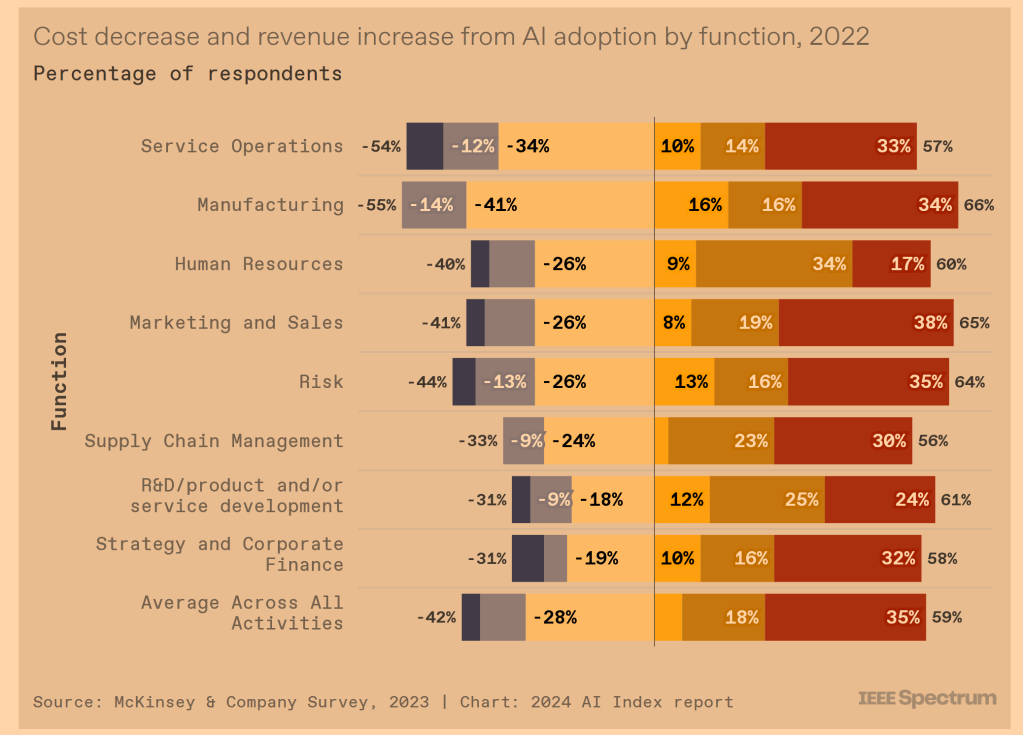

Happiness at work is a bit irrational unless you find purpose in what you do. You are unhappy at work because you have not found “your passion.” Work is not hopeless if an intrinsic and/or social meaning is connected to your labor identity. Then you are not laboring for some unseen bottom-line, for the benefit of others, you are doing work that serves a greater purpose. However, the exploration here is not intended to define happiness or labor identity as right or wrong. Labor identity seems necessary, and we essentialize work, and the discourses of our labor identity become ideology which silences the narratives running contrary. And in this moment in time, post Covid with emerging technology such as Artificial Intelligence, cracks in ideology are more prevalent. This is a project recognizing the network of narratives that influence our labor identity, which is our cultural cosmology. The threads of narrative that are woven together to create our labor identity and the influence of those stories. While I’m exploring primarily professional and skill trades because I’m speaking from my research, as well as my own experience because I’m living and perpetuating/reinforcing the mythology in my work. My methodology (autoethnography) requires a voice from within, but regardless of my limited experience, all types of work are part of this mythology of labor identity.